This year, France was treated to a quintessentially French scandal: a yogurt cartel. On March 12, 2015, the Autorité de la Concurrence, France’s antitrust authority, announced that it was fining eleven companies more than €192 million ($214 million). Together, these eleven companies represented close to 90% of French yogurt production.

From 2006 to 2012, representatives from companies like Yoplait, Novandie, Senagral (Senoble Group), and Lactalis Nestlé, met in private to coordinate price increases on the private-label yogurt, cheese, cream, and dairy-based dessert products that they supplied to France’s biggest supermarkets, such as Carrefour, Auchan, and Leclerc.[1] These large supermarkets are the main outlet for French dairy products, accounting for nearly 92% of all yogurt, cheese, cream, and dairy dessert sales.

During these meetings, which occurred in various hotels, coffee shops, and even their own Paris apartments, the companies discussed the justifications for their price increases (such as heat-waves, lower government subsidies, and higher fruit prices), and the division of their sales volumes. When the group was not conducting their business in person, they were relying on secret cell phones, exchanging hundreds of phone calls and more than thirty text messages. By all accounts, it was a “well-organized cartel” and the Competition Authority spent more than three years investigating the matter after Yoplait came forward as a whistle-blower in August 2011.

The Competition Authority believed the market for these dairy products exceeded €5 billion during 2013 and estimated that the cartel succeeded in driving up prices between 2% and 7%. The impact on the market and the cartel’s sophistication were two of the factors that drove the Competition Authority’s record fine. Of the eleven companies implicated, Lactalis Nestlé received the largest fine, €56.1 million (all fines are included below)[2]. Senagral had been facing a fine of €101.3, but saw its penalty reduced to €46 million after it began cooperating in February 2012. Senagral’s fine was also reduced to account for the company’s financial situation. Yoplait, which General Mills bought in May 2011, would have faced a €44.7 million fine, but ended up completely exempt, having been the first member of the cartel to expose the collusion.

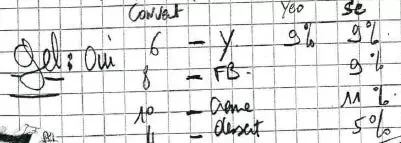

Under a May 2001 French law designed to root out anti-competitive behavior, companies that come forward with evidence of collusion are entitled to full or partial clemency. As part of its cooperation, Yoplait supplied the Competition Authority with notebooks from the meetings that detailed the participants and the decisions made by members of the cartel:

The notes from one such meeting, on July 4, 2007, reflected an agreement to raise the price for desserts by 3%, for yogurt by 4%, and for fresh cheese and cream by 5% on October 1 of that year. Another such meeting, on January 19, 2011 (see below), called for even higher increases: 5% on dessert, 9% on yogurt and white cheese, and 11% on cream.

Thierry Dahan, a member of the Competition Authority, noted that “in the vast majority of cases, it is foreign groups that ask to benefit from [the clemency] procedure.”

Marc Senoble, the Chief Executive of the Senoble group, decried the €46 million fine and said it would force Senagral into bankruptcy.[3] For its part, the Competition Authority noted that it had considered the company’s finances in reducing its fine, and that Senoble had benefitted from a 35% reduction for denouncing the offenses and an additional 30% reduction based on its financial difficulties. Other companies also protested the fines. Despite its relatively small fine of €300,000, the Laiterie de Saint-Malo contested its fine and the facts supporting that fine (the only company to dispute the facts at issue). Lactalis Nestlé did not contest its wrongdoing, but has appealed the amount of its fine, which it categorized as excessive.

John M. Connor, an emeritus professor of economics, believes the fines were too lenient. In his opinion, the cartel stood to make €25 billion in sales during the period in question, making the €192 million fine seem paltry. He added that private-label items are particularly susceptible to collusion, since unbranded products lack any of the trappings or associations created by advertising or brand-loyalty.

Professor Connor has a point, particularly since yogurt and other dairy products occupy such a central part of the French diet and of French life. In 2012, France accounted for 17% of the 140 million tons of milk produced in the European Union. The French language itself reflects this influence. Oh la vache! is an everyday exclamation and vachement bien is a routine descriptor. To make a big production of something is to en faire tout un fromage and to stumble through the lyrics of a song is to chanter en yaourt. To take your business elsewhere is to changer de crémerie. Unfortunately, changing creameries won’t do much good when all the creameries are being supplied by the same cartel.

Price-fixing is just one arrow in the unfair competition quiver. Price discrimination, tying arrangements, monopolization, and restrictive covenants are other examples of antitrust and unfair competition issues HeplerBroom's practice group covers.

[1] Danone, the world’s largest yogurt maker, did not participate in the cartel. Danone does not sell products under supermarkets’ private labels.

[2] All the tables and graphics are from the Competition Authority’s March 11, 2015 decision: Décision n°15-D-03 du 11 mars 2015 relative à des pratiques mises en oeuvre dans le secteur des produits laitiers frais.

[3] Senoble announced it was relinquishing its stake in Senagral in October 2014.

- Partner

Charles N. Insler is an accomplished writer who helps spearhead the firm’s appellate practice. He has briefed more than 15 appeals over the last five years, covering a variety of procedural and substantive legal issues. Mr ...